It shouldn’t be a surprise to hear a woodpecker in a wood. It depends on the circumstances I suppose. In the last week of January, I was in a small wood on the edge of a housing estate in Lewisham – Hillcrest Wood. The sound of a great spotted woodpecker drumming is not yet uncommon, even in London, but here, it felt unexpected, though enormously welcome.

There as one of a group of volunteers with the London Wildlife Trust, I was helping to cut down some Cherry Laurel and Spotted Laurel that had begun to take over, spreading fast and dense across the slopes. As we worked, we kept finding layer upon layer of rubbish. This represented years, perhaps decades, of litter: cans and bottles, chocolate wrappers, fast-food cartons, crisp packets and the skeletal remains of shopping bags, their contents rotted away, with only the worn plastic outers surviving. There were also buried piles of deliberately fly-tipped builder’s waste, rubble, old clothes, sheets and bank cards and old name badges. We even found a rusty pickaxe and the inevitable burnt-out scooter.

With each item that we pulled out I found myself at once feeling a knee-jerk anger at whoever had tossed it there, but also wondering about their lives. Who was it who’d dropped this stuff? What did they do? What were they called? Within this one little wood was a layered snapshot in refuse of London lives; all this rubbish linking back to people who had hung out here, or found themselves passing through, snacking, drinking, smoking.

As I lifted out another gruesome bag of half rotten waste, I heard a sudden, insistent drumming cut through the air – a woodpecker. Nearby, high up in an old sweet chestnut, the bird sounded a staccato reminder that Hillcrest Wood, surrounded by city roads and buildings, wasn’t entirely the preserve of humans.

Later that afternoon, partially hidden beneath the thick, serpent coils of laurel branches, I saw an old stump covered in Jelly-ear fungus. Another sign that despite its tip-like floor, the urban wood, somehow stubbornly retained a tang of its wild character.

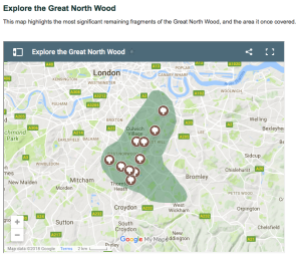

Hillcrest Wood is one of several local woods that are being managed as part of the London Wildlife Trust’s Great North Wood Project. The Trust was awarded a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, as part of the Living Landscapes initiative, to launch the project in 2017. This ambitious, collaborative project will run for four years as the trust works with volunteers, community groups, local woods’ friends’ groups, landowners, and local councils.

Project Officers, Edwin Malins and Sam Bentley Toon see it as “a natural progression from London Wildlife Trust’s involvement in saving Sydenham Hill Wood from development in 1981 and managing the site since 1982.” They told me that, in part, the project was inspired by “The Friends of the Great North Wood, an organisation that was founded in the 1990s by London Wildlife Trust’s current Director of Conservation, Mathew Frith, to campaign against development and mismanagement of Great North Wood sites. They produced a periodical called the Wood Warbler and a number of leaflets about the wildlife and history of the Great North Wood.”

The 1990s Friends of the Great North Wood, in turn, drew impetus from the area’s centuries long woodland status. As an English Nature/London Wildlife Trust leaflet explains: [c 8,000 years ago] “A chain of hills climbed southwards from what is now Deptford, rising to a summit at Sydenham Hill, and dropping to the vales of Streatham and Croydon. This was covered in woodland, and became in time known as The Great North Wood.”

Much of the prehistoric wildwood had been cleared by around 2,500 years ago and by the time of the Norman Conquest, the landscape was largely “a patchwork of fields, pastures, woods, hedges and scattered farmsteads and hamlets.” Yet, for a few hundred years more, pockets of woods and coppices remained, dotted across these hills south east of London, worked and used as raw materials by a variety of residents and landowners from elsewhere, including the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Aside from the few scattered physical remnants of ancient wood that stand today, (nine woods around this part of south London are direct descendants of the Great North Wood), local place names reflect the former dominance of tree and forest here, as Upper Norwood, West Norwood, One Tree Hill, Forest Hill, Honor Oak and Gipsy Hill, amongst others, bear testament.

A once great sweep of trees stretching up and away from the Thames is a little difficult to picture today. Stand somewhere high up like the crest of Westwood Park, a steep road near Forest Hill’s Horniman Museum, and whether you look north towards central London, or back towards the city’s rambling southern suburbs, you’ll have to work hard to imagine an extensive, verdant landscape of fields and woods, with little rivers and streams winding down amongst them towards the great twisting Thames below. The thick forest that stands here today is largely one of concrete, steel and brick.

Strangely, I’ve found that an easier way to give yourself a sense of the historic scale of the ancient woods that once sprawled around today’s South London, is to take a train. The railway line that runs in a U-shape between Victoria and London Bridge has a section that cuts a tree-heavy arc right through the heart of what was once the Great North Wood. It is a stretch that runs between West Norwood and New Cross Gate and is bordered in many parts by quite thickly wooded embankments, where Apple, Ash, Hazel and Hawthorn, amongst more recent arrivals, poke up from rolling layers of bramble.

It is of course a busy London commuter route, so we’re not talking the Forest of Boland Light Railway, yet between the scrap-yards, flats and workshops, it is possible to make out the faint shadow of a lost wood. (Alarmingly, this wonderful linear forest could be under threat if Network Rail carries out its plans to fell thousands of trackside trees across the country as part of its “enhanced clearance” programme. Currently the company has no biodiversity policy, so there is a risk that any tree that happens to be considered to be within falling distance of rails could be chopped down, whether it poses a real safety risk or not).

The shared notion of the long-vanished tree-scape of the Great North Wood is a vital framing device for the project. It is something that stirs the imagination of many who have got involved as volunteers, myself included. As Sam from the Wildlife Trust notes: “We’ve encountered lots of people who are hugely enthused by the Great North Wood, from school children to local historians from wildlife photographers to writers, artists and design students. The ‘vast ghost-wood’ which overlays and interleaves with the modern built environment is a great source of inspiration for many.”

I love the idea of a ghost-wood, in part, because it hints at the haunted forests of folklore and fiction, bringing to mind the northern wilderness of Algernon Blackwood’s Wendigo or the eerie presence of Robert Holdstock’s Mythagos. More powerful still is the sense that where streets and houses and shops now stand, there were once trees and glades and brooks, which with a little encouragement can continue to make their presence felt in the lives and minds of those who tread the same ground today.

For all that, the Great North Wood project is far more than a romantic fancy, or whimsical dream from suburban edge-landers who don’t know any better. There are real, practical benefits to be had from grouping and re-connecting, several local woods under one umbrella project.

In conservation terms there are serious steps that need to be taken. As the Friends of the Great North Wood leaflet puts it:

“There is now an urgent need to take an overview of the Great North Woodlands to conserve their wildlife, and to take measures to minimise the effects of fragmentation, over-use and inappropriate management. Many species of animals and plants once common in these woodlands are now reaching the brink of extinction locally – such as wood sorrel and wood millet – and others have undoubtedly been lost this century – such as nightingale (last heard singing in 1936). The appropriate management of the relict woodlands is of paramount importance, and the extension of woodland cover in appropriate areas necessary to safeguard their future ecology.”

To succeed and to ensure the survival of woodland species such as woodpeckers, purple hairstreak butterflies, stag beetles, oak and hornbeam trees, people have to be engaged with these woods. For Edwin and Sam, establishing such a connection is a key part of the project’s legacy ambitions.

“[the aim is] to revive the Great North Wood in the minds of local people and the wider public. To ensure more consistent management of the woods for the benefit of wildlife: the remaining woods existing as a Living Landscape with many species able to utilise the whole array of woodlands and interconnecting green spaces as a whole.

To encourage people to explore woods that may not be so well-known and to manage access for visitors in the more popular sites in the interests of wildlife (e.g. fencing of sensitive areas, better paths to reduce trampling, boardwalks through wetter areas).”

To this end, the project covers several different sites of varied sizes and situations, all within the once much larger footprint of the ancient wood from where it takes its name. These include: the oak woodland of New Cross Gate Cutting, One Tree Hill, Sydenham Hill Wood – saved from development in the 1980s, Dulwich Wood, Crystal Palace Park (once Penge Common), Beaulieu Heights, Spa Wood, Biggin Wood, Streatham Common and Convent Wood.

Getting involved with a project like this is a wonderful opportunity. Volunteers are not only given the chance to explore these woods more deeply, but to work within them, learning and getting hands-on experience with woodland management, using different tools and techniques. As well as giving individuals new skills and experience, the idea is for them to continue looking after their local woods in the years ahead, well beyond the life-span of the project itself. Edwin says that:

“We are working to develop skills, expertise and confidence to manage local sites with newly formed Friends groups at Hillcrest Wood, Spa Wood and Biggin Wood. We also work with existing Friends groups at One Tree Hill, Grangewood Park and Streatham Common, as well as the Streatham Common Cooperative. These groups will be key to the legacy of the project, as well as the land owners/managers of the woods: five London Boroughs (Southwark, Lambeth, Croydon, Lewisham, Bromley), Dulwich Estate, Virgo Fidelis Convent.”

So far over 100 individual volunteers have taken part during the first few months of the project, with a good number attending regularly at different sites. As one of those volunteers I have been lucky enough to visit five of the woods with the project, and have got stuck into a range of tasks. Although all of the woods are connected historically or geographically with the original Great North Wood, each of those that I have been to has its own quite distinctive character.

Convent Wood, for example, offers a marked contrast to Hillcrest Wood, partly because it isn’t open to the public. This wood lies within the grounds of Virgo Fidelis Convent School, near Norwood Park, between Streatham and Crystal Palace.

Around the back of the school fields, beyond the main Gothic buildings, a narrow path peters out alongside a tennis court and disappears into a clearing amongst tall oaks. Here, during the two sessions I helped at, we built a dead-hedge to protect emerging bluebells and cleared paths to make it easier for a keen teacher to take classes amongst the trees. I can’t say that I’m a natural at making stakes for posts, but I did enjoy cutting back holly, which we used as brash to fill the dead-hedge. Dragging bundled spiky branches to the hedge-site, I was watched by a pair of Robins, darting in and out of the undergrowth.

Further up hill, at the southern end of the wood, past a gathering of shrieking ring-necked parakeets, the trees come to a halt next to the fences and walls of a row of suburban back gardens. I was pleased to note a couple of rough-built wooden swings, evidence that at least a few local children had been unable to resist the temptation to hop over the fence and get into the old wood behind their houses. Perhaps one day, they’ll return on a more formal basis as part of the Great North Wood project.

To find out more, visit http://www.wildlondon.org.uk/great-north-wood

or follow @greatnorthwood on Twitter

Unlocking Landscapes podcast – discussing south London’s ancient woodlands with Sam Bentley-Toon and Chantelle Lindsay from the GNW project.

Cartoonist Tim Bird has recently written and illustrated a delightfully, atmospheric graphic novel on The Great North Wood. There’s a review here.

Trailer for a film on the Great North Wood by @SchulerCJ

Guardian article on Network Rail “enhanced clearance” programme

Pingback: Wandling Free? | Richly Evocative

Great work that sounds very rewarding. I too have experienced similar rage when cleaning beaches in Scotland of lots of plastic stuff dumped at sea. Or just picking up the rubbish in my street. Sounds like a wonderful project to get involved in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Alex, yes very rewarding. And a great way to stop me waiting for the phone to call when in between freelance gigs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Readers might enjoy my short film on the Great North Wood. Here’s a trailer – more screenings announced soon. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-fxLxMRS2LE

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi I’d love to see the finished film. I’ve tweeted the link – I’ll also add it at the end of the post

LikeLike

Fascinating, I didn’t know about the great North Woods, a train trip through South London will never be quite the same……..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds like a valuable and fascinating project.

LikeLiked by 1 person